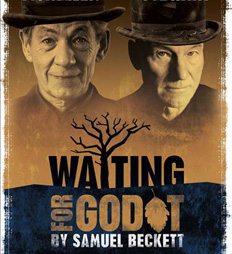

در انتظار گودو

ساموئل بکت (80-1906) پر آوازه ترین و برجسته ترین نویسنده نمایشنامه و ادبیات داستانی معناباختگی، اهل ایرلند بود و در پاریس می زیست. وی غالباً آثارش را به زبان فرانسوی می نوشت و سپس آنها را به زبان انگلیسی ترجمه می کرد. نمایشنامه های بکت از جمله در انتظار گودو(1954 Waiting for Godot) و بازی آخر(1958 Endgame)، بی منطقی، درماندگی، و معناباختگی زندگی را در فرم هایی نمایشی مطرح می کنند که تن به وحدت زمان و مکان رئالیستی، استدلال منطقی و یا پیرنگ متکامل و منسجم نمی دهند. در انتظار گودو مانند اغلب آثار ادبیات پوچی، نمایش معناباخته است، به این دلیل که هم یک کمدی مضحکه آمیز است و هم معطوف به رفتارهای غیر منطقی و بیهوده؛ این نمایش نقیضه سخره آمیزی است که بر باورهای سنتی فرهنگ غرب و نیز سنن و مقوله بندی انواع و دسته بندی نمایشنامه های سنتی و حتی بر تعلق ناگزیر خود به ادبیات نمایشی، ریشخند می زند. گفتگوهای صریح و در عین حال تکراری و بی معنای این نمایشها غالباً خنده آورند و در انعکاس از خود بیگانگی ذهنی و فلسفی و تشویش تراژیک از رفتارهای حماقت آمیز و دیگر انواع دلقک بازی ها استفاده می کردند. آثار داستانی بکت از جمله ملون می میرد Malone Dies) 1958)ونام ناپذیرThe Unnamable) 1960) نوعی ضد قهرمان را ارائه می کنند که در یک کار بی اثر که حتی ابزار خود، یعنی زبان، را هم تحلیل می برد و سست میکند، رفتاری پوچ مانند آنچه یک تمدن به آخر خط رسیده از مردم خود انتظار دارد از خود نشان می دهد. اما معمولاً شخصیتهای بکت، حتی در زندگی های بی هدف به سعی خود ادامه می دهند تا به چیزی که فاقد معنی است معنا ببخشند و ایده ای را که قابل بیان نیست بیان کنند.

نمایش در انتظار گودو دو ولگرد را در بیابان بایری به تصویر می کشد که بیهوده و قدری نا امیدانه منتظر شخص نا شناخته ای به نام گودو هستند که ممکن است وجود داشته یا نداشته باشد و این دو گاهی تصور می کنند که گویا با وی قرار ملاقات دارند؛ به عنوان مثال یکی از آنها می گوید "هیچ اتفاقی نمی افتد، هیچ کس نمی آید، هیچ کس نمی رود، خیلی دردناک است."

"Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes it's awful."

در انتظار گودو در فرانسه نوشته شد و برای اولین بار به سال 1953 در پاریس روی صحنه رفت. ترجمه خود بکت از این نمایشنامه در سال 1955 در لندن اجرا شد. در این نمایش دو پرده ای، استراگون و ولادیمیر در صحنه ای بایر در کنار یک درخت خشکیده منتظر شخصی به نام گودو، که فکر می کنند با او قرار ملاقات دارند، هستند. در طول این مدت برای وقت کشی بازی های شفاهی می کنند که بیننده را بیاد برنامه های طنز شفاهی می اندازد. پس از مدتی پوتزو در حالیکه با طنابی که به گردن نوکرش، لاکی، انداخته او را هدایت میکند وارد می شود. دو ولگرد اول فکر می کنند او گودو است اما پوتزو این احتمال را رد میکند. او لاکی را به شکلی که برای ولادیمیر، استراگون، و تماشاگر ناراحت کننده است وادارد به "رقصیدن" و سپس "فکر کردن" می کند. خطابه طولانی برخاسته از ذهن لاکی کنایه آمیز و نا منسجم است. پس از مدتی ارباب و نوکر، دو ولگرد را ترک می کنند و پسرکی وارد می شود. پسرک به آنها می گوید که گودو نمی تواند آنروز بیاید ولی مطمئناً فردا می آید.

در پرده دوم درخت برگهایی رویانده، اما بجز این تغییر که در دکور صحنه رخ داده است، در رفتار استراگون و ولادیمیر تغییر زیادی مشهود نیست. دوباره پس از مدت زمانی پوتزو وارد می شود، اینبار اما او نابیناست و کاملاً وابسته به طنابی که او را به لاکی بسته است. اینبار لاکی گنگ است اما به نظر نمی رسد که پوتزو متوجه تغییری شده باشد. وقتی ایندو صحنه را ترک می کنند پسرکی که ادعا می کند برادر پسرک دیروزی است وارد می شود و اعلام می کند که گودو نمی تواند امروز بیاید اما "حتماً فردا می آید." و دو ولگرد گرچه عزم رفتن دارند ولی از جای خود تکان نمی خورند.

برگرفته از کتابهای:

برگرفته از کتابهای:

A Glossary of Literary Terms; M.H.Abrams; ed. 7th ترجمه سعید سبزیان؛ انتشارات رهنما

A Survey of English Literature; Amrullah Abjadian; SAMT Publications; 2006

A Survey of English Literature; Amrullah Abjadian; SAMT Publications; 2006

نظر