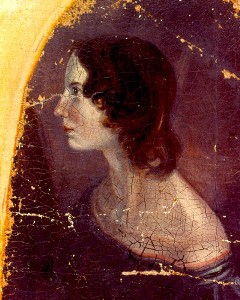

Emily Bronte (1818-1848) was born in Thornton, Yorkshire, in the north of England. Her father, the Rev. Patrick Bronte, had moved from Ireland to Weatherfield, in Essex, where he taught in Sunday school. Eventually he settled in Yorkshire, the centre of his life's work. In 1812 he married Maria Branwell of Penzance. Patrick Bronte loved poetry, he published several books of prose and verse and wrote to local newspapers. In 1820 he moved to Hawort, a poverty-stricken little town at the edge of a large tract of moorland, where he served as a rector and chairman of the parish committee.

The lonely purple moors became one of the most important shaping forces in the life of the Bronte sisters. Their parsonage home, a small house, was of grey stone, two stories high. The front door opened almost directly on to the churchyard. In the upstairs was two bedrooms and a third room, scarcely bigger than a closet, in which the sisters played their games. After their mother died in 1821, the children spent most of their time in reading and composition. To escape their unhappy childhood, Anne, Emily, Charlotte, and their brother Branwell (1817-1848) created imaginary worlds - perhaps inspired by Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726). Emily and Anne created their own Gondal saga, and Bramwell and Charlotte recorded their stories about the kingdom of Angria in minute notebooks. After failing as a paiter and writer, Branwell took to drink and opium, worked then as a tutor and assistant clerk to a railway company. In 1842 he was dismissed and joined his sister Anne at Thorp Green Hall as a tutor. His affair with his employer's wife ended disastrously. He returned to Haworth in 1845, where he rapidly declined and died three years later.

Between the years 1824 and 1825 Emily attended the school at Cowan Bridge with Charlotte, and then was largely educated at home. Her father's bookshelf offered a variety of reading: the Bible, Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Scott and many others. The children also read enthusiastically articles on current affairs and intellectual disputes in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Fraser's Magazine, and Edinburgh Review.

In 1835 Emily Bronte was at Roe Head. There she suffered from homesickness and returned after a few months to the moorland scenery of home. In 1837 she became a governess at Law Hill, near Halifax, where she spent six months. Emily worked at Miss Patchet's shdoll - according to Charlotte - "from six in the morning until near eleven at night, with only one half-hour of exercise between" and called it slavery. To facilitate their plan to keep school for girls, Emily and Charlotte Bronte went in 1842 to Brussels to learn foreign languages and school management. Emily returned on the same year to Haworth. In 1842 Aunt Branwell died. When she was no longer taking care of the house and her brother-in-law, Emily agreed to stay with her father.

Unlike Charlotte, Emily had no close friends. She wrote a few letters and was interested in mysticism. Her first novel, Wuthering Heights (1847), a story-within-a-story, did not gain immediate success as Charlotte's Jane Eyre, but it has acclaimed later fame as one of the most intense novels written in the English language. In contrast to Charlotte and Anne, whose novels take the form of autobiographies written by authoritative and reliable narrators, Emily introduced an unreliable narrator, Lockwood. He constantly misinterprets the reactions and interactions of the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights. More reliable is Nelly Dean, the housekeeper, who has lived for two generations with the novel's two principal families, the Earnshaws and the Lintons.

Lockwood is a gentleman visiting the Yorkshire moors where the novel is set. At night Lockwood dreams of hearing a fell-fire sermon and then, awakening, he records taps on the window of his room. "... I discerned, obscurely, a child's face looking through the window - terror made me cruel; and, finding it useless to attempt shaking the creature off, I pulled its wrist on the broken pane, and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bedclothes: still it wailed, "Let me in!" and maintained its tenacious gripe, almost maddening me with fear." The hands belong to Catherine Linton, whose eerie appearance echo the violent turns of the plot. In a series of flashbacks and time shifts, Bronte draws a powerful picture of the enigmatic Heathcliff, who is brought to Heights from the streets of Liverpool by Mr Earnshaw. Heathcliff is treated as Earnshaw's own children, Catherine and Hindley. After Mr. Earnshaw's death Heathcliff is bullied by Hindley and he leaves the house, returning three years later. Meanwhile Catherine marries Edgar Linton. Heathcliff 's destructive force is unleashed. Catherine dies giving birth to a girl, another Catherine. Heathcliff curses his true love: "... Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest, as long as I am living! You said I killed you - haunt me then!" Heathcliff marries Isabella Linton, Edgar's sister, who flees to the south from her loveless marriage. Their son Linton and Catherine are married, but the always sickly Linton dies. Hareton, Hindley's son, and the young widow became close. Increasingly isolated and alienated from daily life, Heathcliff experiences visions, and he longs for the death that will reunite him with Catherine.

Wuthering Heights has been filmed several times. William Wyler's version from 1939, starring Merle Oberon as Cathy and Laurence Olivier as Heathcliff, is considered on of the screen's classic romances. However, the English writer Graham Greene criticized the reconstructing of the Yorkshire moors in the Conejo Hills in California. "How much better they would have made Wuthering Heights in France," wrote Greene. "They know there how to shoot sexual passion, but in this Californian-constructed Yorkshire, among the sensitive neurotic English voices, sex is cellophaned; there is no egotism, no obsession.... So a lot of reverence has gone into a picture which should have been as coarse as a sewer." (Spectator, May 5, 1939) Luis Bunñuel set the events of the amour fou in an arid Mexican landscape. The music was based on melodies from Tristan and Isolde by Richard Wagner.

The lonely purple moors became one of the most important shaping forces in the life of the Bronte sisters. Their parsonage home, a small house, was of grey stone, two stories high. The front door opened almost directly on to the churchyard. In the upstairs was two bedrooms and a third room, scarcely bigger than a closet, in which the sisters played their games. After their mother died in 1821, the children spent most of their time in reading and composition. To escape their unhappy childhood, Anne, Emily, Charlotte, and their brother Branwell (1817-1848) created imaginary worlds - perhaps inspired by Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726). Emily and Anne created their own Gondal saga, and Bramwell and Charlotte recorded their stories about the kingdom of Angria in minute notebooks. After failing as a paiter and writer, Branwell took to drink and opium, worked then as a tutor and assistant clerk to a railway company. In 1842 he was dismissed and joined his sister Anne at Thorp Green Hall as a tutor. His affair with his employer's wife ended disastrously. He returned to Haworth in 1845, where he rapidly declined and died three years later.

Between the years 1824 and 1825 Emily attended the school at Cowan Bridge with Charlotte, and then was largely educated at home. Her father's bookshelf offered a variety of reading: the Bible, Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Scott and many others. The children also read enthusiastically articles on current affairs and intellectual disputes in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Fraser's Magazine, and Edinburgh Review.

In 1835 Emily Bronte was at Roe Head. There she suffered from homesickness and returned after a few months to the moorland scenery of home. In 1837 she became a governess at Law Hill, near Halifax, where she spent six months. Emily worked at Miss Patchet's shdoll - according to Charlotte - "from six in the morning until near eleven at night, with only one half-hour of exercise between" and called it slavery. To facilitate their plan to keep school for girls, Emily and Charlotte Bronte went in 1842 to Brussels to learn foreign languages and school management. Emily returned on the same year to Haworth. In 1842 Aunt Branwell died. When she was no longer taking care of the house and her brother-in-law, Emily agreed to stay with her father.

Unlike Charlotte, Emily had no close friends. She wrote a few letters and was interested in mysticism. Her first novel, Wuthering Heights (1847), a story-within-a-story, did not gain immediate success as Charlotte's Jane Eyre, but it has acclaimed later fame as one of the most intense novels written in the English language. In contrast to Charlotte and Anne, whose novels take the form of autobiographies written by authoritative and reliable narrators, Emily introduced an unreliable narrator, Lockwood. He constantly misinterprets the reactions and interactions of the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights. More reliable is Nelly Dean, the housekeeper, who has lived for two generations with the novel's two principal families, the Earnshaws and the Lintons.

Lockwood is a gentleman visiting the Yorkshire moors where the novel is set. At night Lockwood dreams of hearing a fell-fire sermon and then, awakening, he records taps on the window of his room. "... I discerned, obscurely, a child's face looking through the window - terror made me cruel; and, finding it useless to attempt shaking the creature off, I pulled its wrist on the broken pane, and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bedclothes: still it wailed, "Let me in!" and maintained its tenacious gripe, almost maddening me with fear." The hands belong to Catherine Linton, whose eerie appearance echo the violent turns of the plot. In a series of flashbacks and time shifts, Bronte draws a powerful picture of the enigmatic Heathcliff, who is brought to Heights from the streets of Liverpool by Mr Earnshaw. Heathcliff is treated as Earnshaw's own children, Catherine and Hindley. After Mr. Earnshaw's death Heathcliff is bullied by Hindley and he leaves the house, returning three years later. Meanwhile Catherine marries Edgar Linton. Heathcliff 's destructive force is unleashed. Catherine dies giving birth to a girl, another Catherine. Heathcliff curses his true love: "... Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest, as long as I am living! You said I killed you - haunt me then!" Heathcliff marries Isabella Linton, Edgar's sister, who flees to the south from her loveless marriage. Their son Linton and Catherine are married, but the always sickly Linton dies. Hareton, Hindley's son, and the young widow became close. Increasingly isolated and alienated from daily life, Heathcliff experiences visions, and he longs for the death that will reunite him with Catherine.

Wuthering Heights has been filmed several times. William Wyler's version from 1939, starring Merle Oberon as Cathy and Laurence Olivier as Heathcliff, is considered on of the screen's classic romances. However, the English writer Graham Greene criticized the reconstructing of the Yorkshire moors in the Conejo Hills in California. "How much better they would have made Wuthering Heights in France," wrote Greene. "They know there how to shoot sexual passion, but in this Californian-constructed Yorkshire, among the sensitive neurotic English voices, sex is cellophaned; there is no egotism, no obsession.... So a lot of reverence has gone into a picture which should have been as coarse as a sewer." (Spectator, May 5, 1939) Luis Bunñuel set the events of the amour fou in an arid Mexican landscape. The music was based on melodies from Tristan and Isolde by Richard Wagner.

Hope

Hope was but a timid friend;

She sat without the grated den,

Watching how my fate would tend,

Even as selfish-hearted men.

She was cruel in her fear;

Through the bars, one dreary day,

I looked out to see her there,

And she turned her face away!

Like a false guard, false watch keeping,

Still, in strife, she whispered peace;

She would sing while I was weeping;

If I listened, she would cease.

False she was, and unrelenting;

When my last joys strewed the ground,

Even Sorrow saw, repenting,

Those sad relics scattered round;

Hope, whose whisper would have given

Balm to all my frenzied pain,

Stretched her wings, and soared to heaven,

Went, and ne'er returned again!

She sat without the grated den,

Watching how my fate would tend,

Even as selfish-hearted men.

She was cruel in her fear;

Through the bars, one dreary day,

I looked out to see her there,

And she turned her face away!

Like a false guard, false watch keeping,

Still, in strife, she whispered peace;

She would sing while I was weeping;

If I listened, she would cease.

False she was, and unrelenting;

When my last joys strewed the ground,

Even Sorrow saw, repenting,

Those sad relics scattered round;

Hope, whose whisper would have given

Balm to all my frenzied pain,

Stretched her wings, and soared to heaven,

Went, and ne'er returned again!

A Day Dream

On a sunny brae, alone I lay

One summer afternoon;

It was the marriage-time of May

With her young lover, June.

From her mother's heart, seemed loath to part

That queen of bridal charms,

But her father smiled on the fairest child

He ever held in his arms.

The trees did wave their plumy crests,

The glad birds caroled clear;

And I, of all the wedding guests,

Was only sullen there!

There was not one, but wished to shun

My aspect void of cheer;

The very grey rocks, looking on,

Asked, "What do you here?"

And I could utter no reply;

In sooth, I did not know

Why I had brought a clouded eye

To greet the general glow.

So, resting on a heathy bank,

I took my heart to me;

And we together sadly sank

Into a reverie.

We thought, "When winter comes again,

Where will these bright things be?

All vanished, like a vision vain,

An unreal mockery!

The birds that now so blithely sing,

Through deserts, frozen dry,

Poor spectres of the perished spring,

In famished troops, will fly.

And why should we be glad at all?

The leaf is hardly green,

Before a token of its fall

Is on the surface seen!"

Now, whether it were really so,

I never could be sure;

But as in fit of peevish woe,

I stretched me on the moor.

A thousand thousand gleaming fires

Seemed kindling in the air;

A thousand thousand silvery lyres

Resounded far and near:

Methought, the very breath I breathed

Was full of sparks divine,

And all my heather-couch was wreathed

By that celestial shine!

And, while the wide earth echoing rung

To their strange minstrelsy,

The little glittering spirits sung,

Or seemed to sing, to me.

"O mortal! mortal! let them die;

Let time and tears destroy,

That we may overflow the sky

With universal joy!

Let grief distract the sufferer's breast,

And night obscure his way;

They hasten him to endless rest,

And everlasting day.

To thee the world is like a tomb,

A desert's naked shore;

To us, in unimagined bloom,

It brightens more and more!

And could we lift the veil, and give

One brief glimpse to thine eye,

Thou wouldst rejoice for those that live,

Because they live to die."

The music ceased; the noonday dream,

Like dream of night, withdrew;

But Fancy, still, will sometimes deem

Her fond creation true.

On a sunny brae, alone I lay

One summer afternoon;

It was the marriage-time of May

With her young lover, June.

From her mother's heart, seemed loath to part

That queen of bridal charms,

But her father smiled on the fairest child

He ever held in his arms.

The trees did wave their plumy crests,

The glad birds caroled clear;

And I, of all the wedding guests,

Was only sullen there!

There was not one, but wished to shun

My aspect void of cheer;

The very grey rocks, looking on,

Asked, "What do you here?"

And I could utter no reply;

In sooth, I did not know

Why I had brought a clouded eye

To greet the general glow.

So, resting on a heathy bank,

I took my heart to me;

And we together sadly sank

Into a reverie.

We thought, "When winter comes again,

Where will these bright things be?

All vanished, like a vision vain,

An unreal mockery!

The birds that now so blithely sing,

Through deserts, frozen dry,

Poor spectres of the perished spring,

In famished troops, will fly.

And why should we be glad at all?

The leaf is hardly green,

Before a token of its fall

Is on the surface seen!"

Now, whether it were really so,

I never could be sure;

But as in fit of peevish woe,

I stretched me on the moor.

A thousand thousand gleaming fires

Seemed kindling in the air;

A thousand thousand silvery lyres

Resounded far and near:

Methought, the very breath I breathed

Was full of sparks divine,

And all my heather-couch was wreathed

By that celestial shine!

And, while the wide earth echoing rung

To their strange minstrelsy,

The little glittering spirits sung,

Or seemed to sing, to me.

"O mortal! mortal! let them die;

Let time and tears destroy,

That we may overflow the sky

With universal joy!

Let grief distract the sufferer's breast,

And night obscure his way;

They hasten him to endless rest,

And everlasting day.

To thee the world is like a tomb,

A desert's naked shore;

To us, in unimagined bloom,

It brightens more and more!

And could we lift the veil, and give

One brief glimpse to thine eye,

Thou wouldst rejoice for those that live,

Because they live to die."

The music ceased; the noonday dream,

Like dream of night, withdrew;

But Fancy, still, will sometimes deem

Her fond creation true.

How still, how happy

How still, how happy! Those are words

That once would scarce agree together;

I loved the plashing of the surge -

The changing heaven the breezy weather,

More than smooth seas and cloudless skies

And solemn, soothing, softened airs

That in the forest woke no sighs

And from the green spray shook no tears.

How still, how happy! now I feel

Where silence dwells is sweeter far

Than laughing mirth's most joyous swell

However pure its raptures are.

Come, sit down on this sunny stone:

'Tis wintry light o'er flowerless moors -

But sit - for we are all alone

And clear expand heaven's breathless shores.

I could think in the withered grass

Spring's budding wreaths we might discern;

The violet's eye might shyly flash

And young leaves shoot among the fern.

It is but thought - full many a night

The snow shall clothe those hills afar

And storms shall add a drearier blight

And winds shall wage a wilder war,

Before the lark may herald in

Fresh foliage twined with blossoms fair

And summer days again begin

Their glory - haloed crown to wear.

Yet my heart loves December's smile

As much as July's golden beam;

Then let us sit and watch the while

The blue ice curdling on the stream

That once would scarce agree together;

I loved the plashing of the surge -

The changing heaven the breezy weather,

More than smooth seas and cloudless skies

And solemn, soothing, softened airs

That in the forest woke no sighs

And from the green spray shook no tears.

How still, how happy! now I feel

Where silence dwells is sweeter far

Than laughing mirth's most joyous swell

However pure its raptures are.

Come, sit down on this sunny stone:

'Tis wintry light o'er flowerless moors -

But sit - for we are all alone

And clear expand heaven's breathless shores.

I could think in the withered grass

Spring's budding wreaths we might discern;

The violet's eye might shyly flash

And young leaves shoot among the fern.

It is but thought - full many a night

The snow shall clothe those hills afar

And storms shall add a drearier blight

And winds shall wage a wilder war,

Before the lark may herald in

Fresh foliage twined with blossoms fair

And summer days again begin

Their glory - haloed crown to wear.

Yet my heart loves December's smile

As much as July's golden beam;

Then let us sit and watch the while

The blue ice curdling on the stream

Source:famous-poems.biz