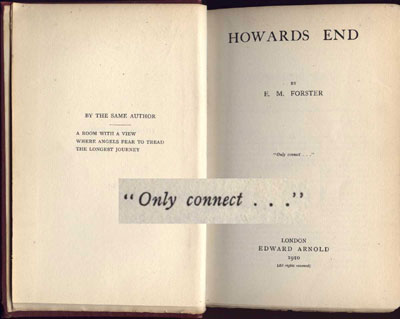

Howards End

Howards End isa novel by E. M. Forster, published 1910, deals with personal relationships and conflicting values.

On the one hand are the Schlegel sisters, Margaret and Helen, and their brother Tibby, who care about civilized living, music, literature, and conversation with their friends; on the other, the Wilcoxes, Henry and his children Charles, Paul, and Evie, who are concerned with the business side of life and distrust emotions and imagination. Helen Schlegel is drawn to the Wilcox family, falls briefly in and out of love with Paul Wilcox, and thereafter reacts away from them. Margaret becomes more deeply involved. She is stimulated by the very differences of their way of life and acknowledges the debt of intellectuals to the men of affairs who guarantee stability, whose virtues of 'neatness, decision and obedience . . . keep the soul from becoming sloppy'. She marries Henry Wilcox, to the consternation of both families, and her love and steadiness of purpose are tested by the ensuing strains and misunderstandings, which include the revelation that Helen has been made pregnant by Leonard Bast, a young, married, lower-class but intellectually aspiring clerk whom the Schlegels had briefly befriended. Her marriage cracks but does not break. In the end, torn between her sister and her husband, she succeeds in bridging the mistrust that divides them. Howards End, where the story begins and ends, is the house that belonged to Henry Wilcox's first wife, and is a symbol of human dignity and endurance.

source: Drabble, Margaret; The Oxford Companion to English Literature; Oxford University Press, New York, 2000.

Read the full text of the novel Howards End

Read more about Howards End

نظر